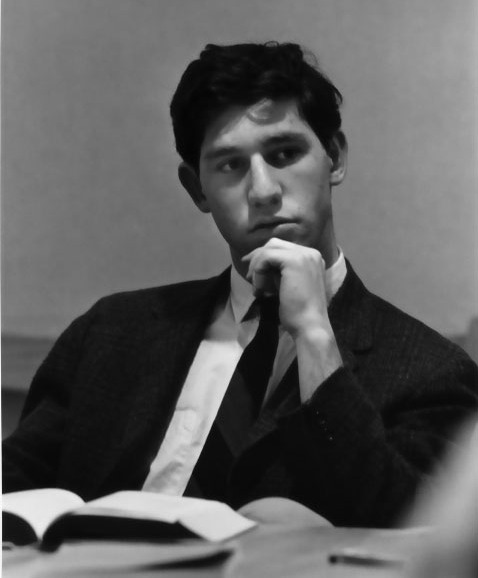

Kenneth Lewis Kronberg (1948-2007). Picture was taken circa 1968.

By MOLLY HAMMETT KRONBERG

DEC. 21, 2010—When you read Ken's essay at the memorial website KennethKronberg.com, bear in mind that he was 19 years old when he wrote it—a senior at St. John's College in Santa Fe, a few months from graduating.

It was for this essay that Ken won the senior thesis prize—for this "Exercise in Analogy and the Power of Imagination," this exploration of poetry, philosophy, and language ambiguous and language diamond-cut.

Remembering Ken

On Easter Sunday, 2007, three days before his suicide, Ken and I and our son, then 22 and himself less than a year past his own graduation from St. John's College (the Annapolis campus), sat in a Leesburg restaurant, having our Easter dinner. Ken and our son talked about this paper; Ken characterized it as a venture into Socratic irony.

The more they talked, the more rapt I was. The paper sounded beautiful and complex. Ken spoke of the defense of poetry—Sidney's, Shelley's, and his own. The defense of poetry and the love of wisdom (philo-sophia). "You really were a poet," I said.

That supper and that conversation were the last time we were together as a family. Our son left that night to drive back to Annapolis, where he then lived. Three days later, on Wednesday, April 11, 2007, Ken committed suicide by leaping from an overpass in Sterling, Virginia.

The Essay

Somewhere in this house, I have a copy of Ken's thesis—but to dig it out would have been a Sisyphean task.

So this past spring, as the third anniversary of Ken's death approached, I asked someone at St. John's to help me get ahold of the essay: I knew the St. John's library would have it, because it had been the senior thesis prizewinner for Santa Fe for 1968—for the first graduating class from Santa Fe, whose campus was as new as Annapolis's was old.

Here is the essay. It helps in reading it to know that Cratylus, one of the interlocutors in Plato's dialogue named after him, was a protégé of Heraclitus, the Ionian pre-Socratic philosopher so little known and yet so beloved of Hegel and Engels—and so often cited by Lyndon LaRouche.

(Indeed, it is from The Cratylus [line 402a] that we have the famous dictum of Heraclitus—namely, that one cannot step twice into the same river: potamois tois autois embainomen te kai ouk embainomev—we step into and do not step into the same river.)

Heraclitus, Plato, Flux, and the Eidei

According to Aristotle in The Metaphysics, Plato himself endorsed the Heraclitean notion of flux (see Heraclitus's other memorable line—panta rhei kai ouden menei—everything flows and nothing abides) as applied to the material world, and concluded therefrom that the material world is unknowable.

According to Aristotle, it was from that circumstance that there arose Plato's notion of the eidei, the forms, the ideas—the realm of Being and of the things that Are, as opposed to Becoming and the things that are Passing Away—the conception whereby Plato asserted the realm of the eternally knowable and unchangeable.

In the worldview of Lyndon LaRouche, however (Lyndon LaRouche, in whose organization Ken spent his entire adult life), Aristotle is an evil figure, the Father of Lies. Someone like Ken, someone who has actually read Aristotle, will take a more balanced view, and accord Aristotle a hearing. After all, Aristotle studied with Plato at the Academy for 20 years, roughly, from 367 BC to 347. He might be supposed to know something of Plato, even if he ultimately disagreed with Plato's conclusions.

Perhaps this relationship between Plato and Aristotle—comrades in the love of Wisdom (Sophia) and the search for Her, disputants along the way—a relationship so clearly portrayed in Raphael's School of Athens, was how Ken Kronberg thought of the two men. Perhaps that is why he used the School of Athens so many times on the cover of LaRouche magazines—The Campaigner first, and later Fidelio— slyly undercutting the LaRouchean dogma (so slyly that LaRouche and his associates thought Ken was simply agreeing with them).

Perhaps the same concerns dominate the articles Ken wrote for LaRouche publications over the years—including, for instance, Ken's 1995 article on "Some Simple Examples of Poetic Metaphor" and his article of December 1999 on "How To Read Poetry: John Keats' 'Ode on a Grecian Urn.'"

Words, Things, and Poetry

It helps, in reading Ken's essay, to know that The Cratylus deals with the problem of language: Are words connected in some necessary way to the things of which they speak, or are they arbitrarily assigned sounds? Using a Greek play on words, Is there a logos—an account, a reason—for logoi (words), or are they merely alogoi—irrational, arbitrary? In other words (to continue the wordplay), what is the relationship between thinking, and speaking, and being?

Naturally, this is of the greatest interest to the poet, for in poetry, the very sound of the word has meaning—apart from, or as part of, the meaning of the word?

In this essay, the great conundrums of the One and the Many, of Being and Non-Being, of the relationship between Being and Mind—in short, the subject-matter of Plato's dialogue The Parmenides—make their appearance, slipping in and out of the discussion concerning philosophy and poetry; expressed in the figure of Cratylus and in the presence of his non-present mentor, Heraclitus; in the discussion of the divided line of The Republic, in the "dialectic of the mind."

The essay assumes familiarity with all the thinkers and great books quoted (and not quoted); all those spoken of, those alluded to, and those present in the shadows, never mentioned but incorporated.

St. John's College

In some sense, Ken's essay is about St. John's—about the Great Books program, about the meaning of joining in the great enterprise of Western thought, the great dialogue that spans the centuries: What is Being? How do we know, what can we know, what do we know? Is there a necessary connection between Being and the Good? How must we live our lives?

The great dialogue insists on one constraint: To participate, we must listen. We must hear what the great minds and the great books—and the not-so-great minds and the lesser books—have to say. It is impermissible to reject, to denounce in a fury, without having once heard. And if we have heard, then it is unnecessary to denounce—it is possible to argue.

It is useless to insist on one's own primacy and inerrancy—we gather to talk, not to assault. So to claim (for example) that Aristotle is the most evil man of his generation, or any other such folly, immediately betrays one as a stranger to the dialogue, a stranger to the eidei.

Ken's essay points toward the radical assertion made by Heraclitus's opposite number, the Eleatic Parmenides: It is the same thing to think and to be: to gar auto noein estin te kai einai. Parmenides insisted: Being. Heraclitus insisted there is no such thing: There is change only.

Noein Einai—to think

is to be. One might take this as emblematic of Ken Kronberg, who he was and

what he did. And of course, the terrible consequence: Where thinking was no

longer possible, it was no longer possible to be.